Diversification is the gold standard of the modern age of investing. Its roots can be traced back to the financial giants of the 20th century, most notably one Jack Bogle, who introduced the world to the index era with the founding of Vanguard in 1975.

Since then, the index fund has quickly displaced all other investment vehicles in an insatiable gobbling of market share. It is estimated now that index funds hold somewhere between 20% and 30% of the entire US equities market.

This is no accident. Index funds promise low costs, easy access, and high liquidity. However, the real reason they have become so prevalent is more fundamental: investors holding the market can expect to enjoy not only greater passivity, but also reliably higher returns in the long run.

Obviously, this is not because the market ever outperforms any given handful of high yielding stocks. It’s because the probability of successfully holding any such handful over time is exceedingly small.

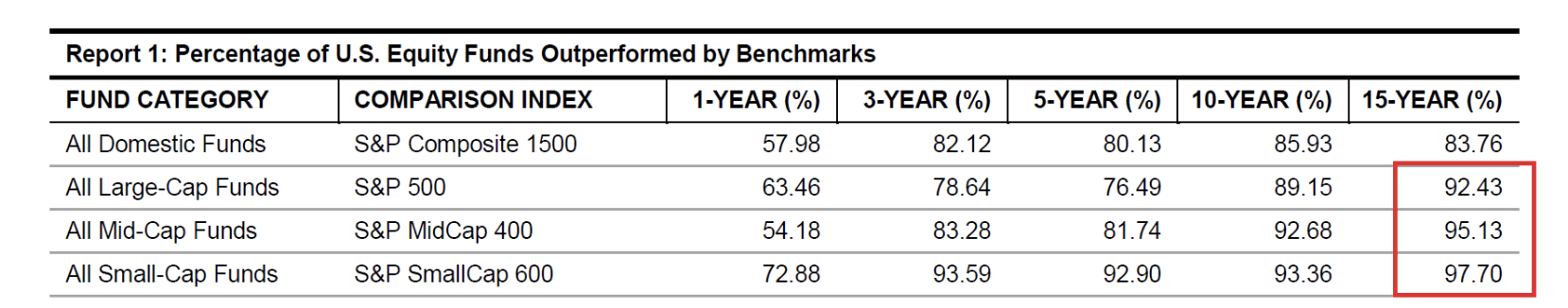

This fact underlies the notorious failures of professional stock pickers who seek alpha. With a few interesting exceptions (the medallion fund is a fascinating, if non-replicable, case study), the rule has been evidenced by unbecoming data indicating how few managed funds beat the benchmark over time and various, damming studies like one featured in Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow which showed the performance of investment advisors in one firm had year over year correlation coefficients of zero (that is, in the fullness of time their performance was no better than chance).

Scorecard for actively managed funds vs. the benchmark as of mid 2018. https://www.cornell-capital.com/blog/2020/02/medallion-fund-the-ultimate-counterexample.html

All this speaks to the genius of Jack Bogle’s approach and the broad applicability of his doctrine of diversification.

Dilution by Default

The problem is that Jack’s wisdom has gradually become background knowledge for many investors, and has, as such, slowly slipped from the arena of scrutiny.

If it hadn’t, a few things would be clear.

For one, diversification is not a solution to the problem of securing alpha, but an avoidance of it. To hold the market is essentially to retreat to the position that “something is better than nothing.” The water in the river might sometimes make you sick, but it is better than dying of thirst. But to drink from the river is not a solution to the problem of thirst the way boiling the water would be.

For another, to assume that diversification is a universal prescription is to ignore the specific circumstance that would make it a sound strategy — namely, nearly intractable complexity. If the technology needed to boil water were so advanced that any would-be inventor would likely die of thirst before discovering it, drinking water directly from the river makes good sense.

This is to say that a proactive solution in an environment with solvable problems is obviously superior to the default position; if building a fire that can be used to boil water is trivial, drinking from the river is foolish. Put another way: if you can solve a problem, you should.

Thus, to know whether to adopt the doctrine of diversification, an investor must first survey the investment landscape and ask to what degree its problems are solvable. If the answer is “to a low degree,” default to diversification. If the answer is “to a moderate or high degree,” endeavor for more.

And here is the crux of the matter. In today’s investment landscape, only a narrow view of investment opportunities would suggest alpha problems are too hard to solve to be worth pursuing. To diversify anyway is thus to dilute return and suffer exponential opportunity cost over time.

Seeking Alpha

Several objections may arise.

The first might be that most people do not find themselves with the time needed to survey the landscape, and so can create no map that will reliably return them alpha. And so most should diversify.

The second might be that even if one has the time to survey the landscape, there are no obvious landmarks to journey to. The market’s information is complete and its resource allocation efficient, and so expected outcomes for alpha seekers must be bleak. This is analogous to assuming all precious resources have been mined, and so one better not set off looking for gold. As the old economics joke goes:

Two economists are walking down the street and pass by a hundred-dollar bill without picking it up. A little while later one turns to the other and asks, “was that a hundred-dollar bill on the ground?” To which the other replies “No. If it was, someone would have picked it up already.”

We can begin with this second objection.

Real estate as an asset class alone is evidence enough that all markets are not perfectly efficient. Andrew Carnegie is reported to have stated 90% of millionaires got that way through real estate investment, and, apocrypha aside, there’s a good reason why this is generally true.

Real estate investment is knowable, scalable, and replicable. As such, diversifying would make little sense – ask a real estate investor why they don’t just hold a REIT and you will receive an incredulous answer (returns of the average investment dwarf those of the best performing REIT).

That may be the most obvious region on the landscape where seeking alpha is not futile, but there are many others. University students who have earned considerable sums in low-cost ventures ranging from online services to basic arbitrage of goods and services, for example, can be easily identified.

What’s more, the very idea that we can and should approach perfect efficiency is fundamentally flawed. Innovation has already been tempered by too many investors hedging their bets by adopting the default position (buying the index). As risky ventures are the reason the market rate of return reliably compounds to begin with, that loss of dynamism is regrettable.

If it were true that there are no longer solvable problems (or that there soon may no longer be), then the market would be doomed to fail. Ironically, by holding the index an investor is implicitly making a bet to the contrary. And so only a moderation of that approach avoids circular reasoning: I hold the market because the market grows, and the market grows because I hold the market.

Here is also where the landscape analogy breaks down. While physical resources may be exhausted or lose their scarcity, on the economic landscape resources are ideas which are not only inexhaustible, but inflationary. The only obstacle, then, is a wholesale default to diversification.

And now to the first objection: that those without much spare time to seek alpha should diversify as, after all, something is better than nothing. This is also superficial in reach, mainly on two accounts.

The first is a problem with what consists of “something.” Let’s stay you start with an initial investment of fifty thousand, an investment horizon of forty years, and the earning power to contribute one thousand a month for the period. Assuming a 7% return (with 3% yield variance), that works out to just over three million dollars over the life of your investment horizon. The sum is certainly better than nothing. But is it enough?

With a 2% base rate of inflation over that same period, in today’s dollars that nest egg would be closer to 1.8 million by retirement. So, the error is to assume that the market rate of return is generally sufficient. It may be passably sufficient to ensure a basic retirement, but it is grossly insufficient to achieve greater levels of security (or enjoy any of your wealth in vital years).

The second account is that diversification is not the only passive option. This is the other side of the “something is better than nothing” rationale. Syndication, turnkey investing, house hacking, and peer to peer lending are all examples of strategies that do not require the full attention of an investor but still promise significantly better returns than a benchmark.

Now, it’s true that not all these alternatives are entirely passive. But then, neither is traditional diversification. Even indexed holdings must be monitored and rebalanced over time, and there are questions at inception about what specific strategy of diversification best aligns with risk tolerance and the state of the global economy that warrant answering.

In the end there is only one truly passive option, and that is to do nothing at all. That we should aspire above that level of passivity is clear. Further aspiring somewhere above the default activity should then be no great leap.

Conclusion

Jack Bogle’s approach was brilliant. But for the individual investor, there is a limit to its applicability.

If you have a little and want a lot, don’t diversify. If you have a lot and want a lot more, diversify in moderation. It makes sense to leave some troops at home to defend the citadel, but don’t station the entire army there.

Pure diversification is therefore for those who either have a lot and don’t seek much more, find themselves nearing the end of an interval, or are unwilling or unable to solve problems in fruitful climates on the investment landscape.

For the rest of us, diversification is dilution.

Recent Comments